In his postmodern novel The French Lieutenant’s Woman, John Fowles tells us that the heroine, Sarah Woodruff, was “the perfect victim of a caste society. Her father had forced her out of her own class but could not raise her to the next. To the men of the one she had left, she had become too select to marry; to those of the one she aspired to, she remained too banal.”

It takes but a single lap of any racetrack in the stunning new Camaro Z/28 to understand that it, too, has been elevated beyond its traditional station. It bristles with accoutrements, from the dry-sump, 505-hp LS7 V-8 to the carbon-ceramic brakes and Multimatic-developed dampers. (And what everyone on this test referred to as those tires—but more on that later.) Around a road course, the Z/28 substitutes typical pony-car histrionics with the icy composure of a fettled SCCA sedan racer. Feel free to believe most of the hype.

READ MORE: The 2014 Chevrolet Camaro Z/28 is a monster

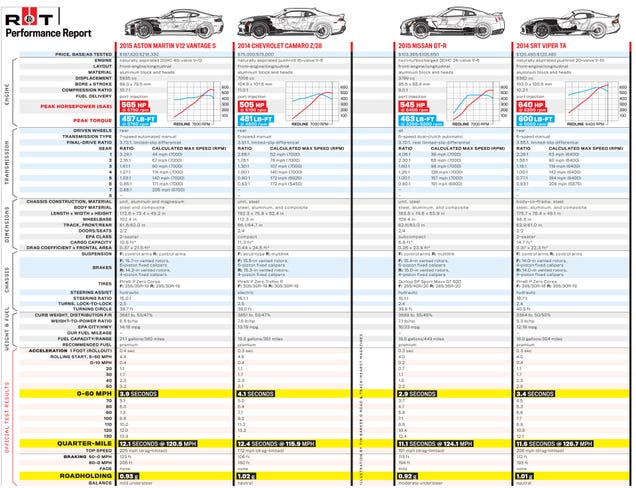

At a robust $75,000 before the inevitable dealer markup, however, the Z/28 will challenge the preconceptions of potential buyers as strongly as it does their pocketbooks. It costs significantly more than its supercharged ZL1 sibling, yet it falls behind on a dyno or a drag strip. Base equipment doesn’t include air conditioning. It would be possible to make a better impression on the neighbors by selecting something cheaper, like a Mercedes-Benz C63 AMG or a BMW M3.

EXPAND

EXPAND

What we have here is a bit of a misfit. A purpose-built corner carver sharing a showroom with similar silhouettes that fetch a fraction of its shocking sticker. You might think the engineers responsible are dreamers—but they aren’t the only ones. There’s an island’s worth of misfit cars out there, dream machines that exist for the moment when they roll onto pit lane.

Consider the Dodge Viper TA: stiffer suspension than a base Viper, track-focused Pirelli rubber, uprated brakes, and aero tweaks. Did anyone really think the standard Viper wasn’t purposeful enough? Apparently, and that someone cared enough to turn up the wick on what was arguably the most track-focused production car available. The result is the Time Attack, a Viper that sounds ready for the world’s brashest autocross. What about the Aston Martin V12 Vantage S? Any sensible person would prefer that brilliant engine in, say, a DB9, but not everyone is sensible. So now we have a Supermarine brute combining the marque’s shortest wheelbase with 565 hp and a mandatory single-clutch seven-speed automated manual.

The argument—there must always be argument—wasn’t over if the Z/28 was good, but why.

READ MORE: Dodge Viper, the prodigal snake, comes home

Nor can we forget one of the most iconic misfits ever built, the Nissan GT-R. At rest, the big Nissan crackles and pops with subtle mechanical noises; once on the move, it rips off an 11.1-second quarter-mile that leaves even the Viper gasping in its wake. It’s undeniably good, though sadly we couldn’t get the better-suspended Track Edition, forcing us to go with the “normal” version of a notably supernormal car. Which, famously, is also a $105,000 car that sits next to $13,000 sedans in the showroom and shares their humble badge.

The Z/28 appears to have the right stuff to join that elite crowd, the happy few modern cars with the courage of their road-course convictions. But when you’re asking 75 grand for your product, “appears” won’t cut it.

So let’s find out the truth. With help from two-time Daytona Prototype champion Alex Gurney, we took this gang of four to the brand-new, purpose-built Thermal Club outside Palm Springs. Is the Z/28 really good enough to shine in this company?

EXPAND

EXPAND

IF YOU WANT TO LEARN an unfamiliar track in a hurry, there are few better ways to do it than with a GT-R. The Nissan is known for a singular ability to warp space between one corner and the next, but it truly excels in its docile handling and foolproof midcorner balance. My first few laps of Thermal’s 1.8-mile track, therefore, are spent in the GT-R. In this group, it’s woefully short on grip; the Dunlop SP Sport Maxx GT 600 tires are road-optimized run-flats, unable to match the specialized rubber of the other cars here.

Oddly, the Track Edition comes with the same rubber, so it would have done only marginally better in this regard. At least these tires are predictable, letting Road Test Editor Robin Warner abuse the car’s great chassis and low adhesion into a series of slides for the crowd.

READ MORE: Ford Focus ST – Long-term wrap-up

The steel brakes can also feel slightly inadequate, with Senior Editor Josh Condon referring to them as “cotton candy.” When the GT-R debuted, the big gold Brembos were the bee’s knees, but the world has moved on. It doesn’t help that this is the heaviest car here, outmassing the Camaro by 38 pounds. Unfortunately for the Nissan, the Camaro has carbon-ceramic rotors and the Viper has 525 fewer pounds of car to slow.

On the hairpins that mark both ends of Thermal’s Alan Wilson-penned layout, it’s easy to blow past the brake zone into the runoff. It doesn’t help that the GT-R crests 130 mph on the back straight with absurd ease, the double-clutch transmission shrugging off the heat and tugging the big coupe along seamlessly. Then it’s time for the next corner, and, as always, you can feel the car distributing torque to fix your mistakes, address your sloppy apex, and reliably blur the Chiclets.

READ MORE: In 4 laps, I learned 5 things about the GT-R Nismo

The Nissan has set the standard for road-car track excellence for so long, our testers don’t immediately warm up to the idea that it’s not going to blow the others out of the water. The power and drivetrain are superlative, but in the space between straightaways, the GT-R loses time to the Viper and Camaro.

EXPAND

EXPAND

“With four Crays’ worth of processing power, the GT-R should be all magic, all the time,” suggests Senior Editor Jason Cammisa, “but like anything run by computers, the Nissan was bound to become obsolete. Just didn’t think it would be this quickly.”

The Viper may have more body roll than some would like, but it’s the perfect tool for inhaling pavement.

From the Nissan into the Aston, and it’s a completely different world. The noise from the 5.9-liter V-12 alone is enough to make you a believer. Senior Editor John Krewson: “This, as the Brits say, is not a motor that had to buy its own furniture.” A shame, then, that Aston didn’t buy it a better transmission. Each pull of the paddles summons … well, first it summons nothing, but eventually there’s a prehistoric “clunk” from the single-clutch Graziano gearbox. It’s the price the car pays for popularity; last year’s V12 Vantage had three pedals and a perfectly serviceable six-speed. But customers wanted an automatic, and no other automatic would fit. Therefore we suffer the inelegant Speedtronic automated manual. At full throttle, with the hugely charismatic engine snarling its way to 7000 rpm, each shift takes a subjective eternity— it’s quick but doesn’t feel it. It’s accompanied by a jolt to the neck as the clutch grips the next gear.

Get used to the drivetrain, however, and it’s all smiles from there on out. Executive Editor Sam Smith notes that the front end takes encouragement with the brakes in order to bite, and Condon agrees; this is one car where trail-braking is mandatory. “Connected to your brain through the fingertips” is Condon’s verdict on the steering, and Cammisa’s notes agree: “Inspires immediate confidence… . Within three corners, I’m comfortably manhandling the Aston into drifts through every corner. It’s a level of confidence that I don’t come close to in the other cars.”

READ THIS: The unacceptable danger of modern track-day coaching

The Vantage can’t touch the straight-line speed of the Nissan or Viper, but it’s so visceral that one visitor who rode in each car, and with the same driver, proclaimed that she thought the Aston was by far the quickest.

EXPAND

EXPAND

Not so. Still, it’s the biggest experience. Were it saddled with the interior of an old Mustang—or, for that matter, a Seventies Aston—it would be the largest personality in the test. The fact that our test car was loaded to the gills with wine-tinted carbon fiber and quilted leather seats only solidified its position as the machine most likely to be remembered days later. In that light, even the antiquated transmission wasn’t all that bad. It was certainly characterful, which is what Astons are supposed to be.

As are Vipers, but in a totally different way. To begin with, the TA is the only car here that injured every single driver and passenger who tried it. Blame the wide sills that don’t even pretend to insulate the occupants from the side-routed exhaust pipes. Some of us were burned once, others twice. It didn’t keep us from driving the car until the brakes faded and the coolant temperature soared. “It takes more effort than the others to truly appreciate,” Warner notes, “but if you can work on its level—wow!” Cammisa amplifies the statement: “At anything less than the limit, it stinks.”

READ MORE: Could you live with a Dodge Viper?

Yet the Viper captured my heart. The seating position that failed to work for most of the staffers was perfect for me, and the controls fell, as the cliché goes, readily to hand. It just made sense. On the move, it’s the composed confidence, and competence, that impresses. The steering is true and trustworthy, combining solid turn-in feel with enough ratio to catch back-and-forth oversteer in Thermal’s midspeed chicane. It’s a long, wide car, and sprung softly enough to allow big weight shifts across each tire’s contact patch, but it never surprises. The SRT is the most honest and direct car of this group, never doing more than what you ask and responding to each input with a measured response.

The Z/28’s amazing turn-and-stop abilities are so far above those displayed by the rest of our group, it’s almost unnerving.

EXPAND

EXPAND

That said, the limits of the Viper are objectively high enough, and it approaches corners at such an extraordinary speed, that you can’t not be cautious. The SRT’s hot-rod vibe is an acquired taste, and Web Editor Alex Kierstein, a newcomer to Vipers in general, is less than enthusiastic: “Everyone says it’s so much better than older Vipers… . Count me out for versions 1.0 and 2.0, then.”

The brakes also came in for criticism, being alternately prone to a stiff pedal (from pad float) or a long one (from boiling fluid) as our day went on. Track-optimized pads and fluid would likely solve the issue.

READ MORE: Aston Martin Vantage V12 S – First Drive

At heart, the Viper is flawless fundamentals. The car is engineered from the ground up for this sort of work, and it shows. It has an unstressed, massively powerful engine; a low center of gravity; wide tires; and enough power assistance to render it relatively low-effort to drive. It’s loosely suspended but easily manipulated. At speed, with that distant nose sniffing for corner entry, the V-10 roaring a strident but truck-like and inharmonic song through long gearing, the cockpit comfortably wrapped around you, the Viper delivers without compromise, excuse, or fail.

EXPAND

EXPAND

If only it had tires like the Camaro’s. The Z/28 was developed from the jump to work with the mighty Pirelli P Zero Trofeo Rs, and it shows. GM claims that the Pirellis generate so much grip that early prototypes experienced slippage around the 19-inch wheels during braking. Chevrolet addressed the issue by media-blasting a rough, high-friction surface onto the section of the wheel that mates with the tire, leaving the Z/28 free to exploit all the available stick. Which it certainly does.

READ MORE: In the desert with the Local Motors Rally Fighter

“I love this thing,” Condon’s notes rave. “SO MUCH GRIP.” Cammisa’s also a fan: “I can’t remember ever driving a car this heavy with this much grip on turn-in and on the way out—it sticks, always.”

Sure enough, my first lap in the Z/28 is a comedy of errors, as I vastly underestimate the available braking power and cornering grip. It takes a few tries to get used to the way the Chevy turns. There’s no sidewall flex, no tread slip. Only the front-end tug as each wheel movement is instantly translated into lateral force.

EXPAND

EXPAND

The Z/28’s amazing turn-and-stop abilities are so far above those displayed by the rest of our group that it’s almost unnerving. (Even test-lapper Alex Gurney, a man as comfortable bump-drafting a Daytona prototype at 200 mph as most of us are tooling to the grocery, takes a second set of laps to refine his thoughts on the car. The combination of carbon brakes and Pirellis doesn’t immediately sink in.)

READ MORE: Clueless dealers do the Toyobaru twins no favors

It’s more than the tires, of course; the Camaro’s expensive, pro-grade, spool-valve shocks help ensure that the Trofeo Rs spend most of their time glued to the ground. Aero tweaks including a new spoiler, a new undertray, and one massive underbite of a splitter—plus a flow-through bow-tie badge that Chevy will doubtless play up to give its customers the illusion of understanding aerodynamics—gift the Camaro with a claimed 150 pounds of downforce at 150 mph. For a street car, that’s huge.

The Viper is the only car here that injured everyone who drove it … Which didn’t keep us from driving it until the brakes faded.

EXPAND

EXPAND

It’s also necessary, because the base Camaro, like most cars, generates lift at high speed. Thermal’s relatively low-speed layout (a faster, longer track addition is under construction) wasn’t enough to paint a full picture of the Chevy’s aero behavior, but we got a nice glimpse. And all the track development time that GM spent with the Z/28 is evident in the arrogantly cultured manner with which the car swallows an exit curb under full throttle.

“This Camaro is simply too good for a fan base that misspells the model’s name half the time,” Krewson notes.

The rest of the Z/28 is standard issue, with the exception of the mighty LS7 V-8, sourced from the outgoing Corvette Z06. That engine’s 505 hp feels nearly as strong here as it does in the 700-pound-lighter Vette, but in this company, it just seems adequate. The Nissan and Viper can dust it without breaking a sweat; the Aston sounds like it’s actively bullying the Camaro around the playground.

EXPAND

EXPAND

This is a hot romance in the making—but then it gets too hot. Although ambient temperature is barely in the 80s, three hard laps are enough to send the Camaro’s oil temperature around the dial and beyond the 300-degree mark.

“Unacceptable in any high-performance street car,” Cammisa gripes, “especially one with this much track capability.” The Aston and Nissan have been getting hot, but not like this. It’s a reminder that the Z/28 is fundamentally a development beyond what was originally intended for the Camaro platform.

READ MORE: The case for the dogleg

The argument about the Chevrolet is raging as Gurney settles in for his timed laps. To no one’s surprise, the Viper is by far the fastest, clicking off a 1:23.4. Repeat the mantra: less weight and more power, lower center of gravity and wider tires. But second place? The Camaro, surprising everyone.

The data tell the tale: In the entry phase of the corner, the Z/28 is brilliant and remarkably fast. It’s enough to put a gap of 0.3 second back to the GT-R. The Nissan can exit corners and build momentum in unparalleled fashion, but those qualities can’t make up for the significant disadvantages in braking and traction.

In last place, with a 1:26.6, is the Aston. We expected that, even if the aforementioned visitor didn’t. Blame it on a combination of mass and tire width. The data traces for the Vantage show it accelerating harder on corner exit than the other cars, but from lower speed; the Aston requires a deliberate approach on entry and in midcorner, which costs time.

EXPAND

EXPAND

Big, sonorous V-12s are wonderful, but they can’t fix everything.

When polled, Gurney comes out strongly in favor of the Camaro, citing its front-end grip, strong brakes, and vice-free balance. The Viper doesn’t impress him; although he admits that it’s the closest thing to a race car present, Gurney is irritated by the TA’s relatively soft suspension. It’s an annoyance he repeatedly hammers home: too much front-to-back pitch to consistently put the car where he wants it. Still, Gurney draws a clear distinction between the Camaro/Viper juggernaut and the backmarkers, criticizing the Nissan’s softness and lack of stick. The Aston, predictably, gets notes on its transmission.

READ MORE: Egan on drivers and their signature helmets

So that’s the data. But as is often the case, it can be taken two ways. As the test comes to a close, the staff divides into two groups. On one side is the pro-Z/28 faction, led by Smith: “We’re in the desert, so I’ll forgive the heat soak. The rest of the car is just … sorted.”

On the other side is the good-car-with-great-tires clique, and sadly, while I’m the president of that club, I’m also the only member. To me, the Z/28 seems a solid competitor to the outgoing Ford Mustang Boss 302, but for nearly twice the money. (Interesting point. Incorrect, but interesting —Ed.) I make all the arguments that have dogged the Camaro since its introduction: too big, too heavy, bathtub visibility, indifferent steering feel.

EXPAND

EXPAND

It’s all in vain. The verdict is in, and everyone from our least experienced staff member to a two-time Grand-Am champion agrees. In this company, the Z/28 feels perfectly at home. It might be too expensive for what you get, although one suspects that Chevrolet will sell every one it can build. And the car might even be flattered by what is surely the finest tire package ever fitted to a mass-market production car. But it has the heart, the mojo, and the all-around ability to shine in virtually any gathering. Among these cars, on this track, it’s worthy of another Fowles quote: “A gentleman in a gentleman’s house.”

This misfit is not what the Camaro has always been. Whatever the Chevy once was, however, it’s now one thing: outstanding.

EXPAND

EXPAND

Source http://kinja.roadandtrack.com/battle-of-the-misfits-the-camaro-z-28-versus-the-world-1649916811

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

YouTube

RSS